For the past six months, Italians have been floating from triumph to triumph.

In July their men’s football team became Europe’s champions beating England at home in London’s Wembley Stadium.

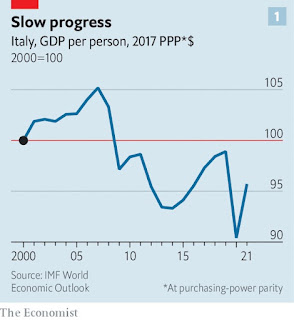

Italy has meanwhile started to be governed by an internationally respected prime minister, Mario Draghi, with a huge parliamentary majority that allows him to turn his projects swiftly into law. Supported by an effective vaccination campaign, the economy is recovering strongly. On October 28th Mr Draghi, a former president of the European Central Bank, forecast economic growth this year of “probably well over 6%”, though few expect Italy’s GDP to regain its pre-pandemic level until 2022, well behind America and Britain, among others. But Standard & Poor’s, a rating agency, has revised its outlook for Italian debt from stable to positive, and Italians can look forward to a period in which their government will be in a position—under an obligation, indeed—to spend liberally for the first time since the days of the post-war, American-funded Marshall Plan.

Italy

stands to be the biggest beneficiary in absolute terms of the EU’s

post-pandemic recovery project. From the core Recovery and Resilience Facility

alone, it is due to receive €191.5bn in grants and loans. Such an influx of

cash cannot help but have an impact on an economy that, even before covid-19,

had barely grown this century, thanks to a combination of slow growth in even

the best years and big declines in the bad ones. Real GDP

per person was 1% lower over the period, compared with increases of 16% in

France and 24% in Germany. Oxford Economics estimates that over the next three

to four years the EU’s recovery project will add on average a helpful annual 0.5

percentage points to Italian GDP growth.

Italy’s reform program is not the problem; that is ahead of schedule. In May a package was approved that simplified a wide range of bureaucratic procedures. And a shake-up of the criminal-justice system is about to be implemented. A further reform, focusing on civil justice, is in the pipeline. Officials say that legislation to promote competition is also coming soon.

The problem is with investment. The outstanding foot-draggers appear to be the ministry of tourism, which at the time of the report had yet to implement any of the six investments for which it is responsible; and the department for ecological transition, which had implemented only one.

Looking beyond the end of this year, one doubt arises. It concerns the fate of legislation after it is handed out for implementation at the sub-national level. “In Italy, the intention of policies is all too often lost in translation,” says Paolo Graziano, who teaches political science at the University of Padua. There is a shortage of the necessary project-management skills among officials charged with implementing complex programs—a shortcoming the Draghi government says it has begun to address. But another reason, says Fabrizio Tassinari of the European University Institute in Florence, is that “secondary legislation becomes hostage to vested interests, from local authorities to trade unions.”

On October 18th mayoral candidates from the Democratic Party

(PD) were elected in Rome and Turin, completing a clean sweep of Italy’s

biggest cities by the center-left. But the PD and its allies are weaker in the

provinces. Polls continue to suggest that Italy’s next government will be a

coalition dominated by two parties that have long been critical of the European

Commission: the Brothers of Italy (FdI) party, which has links to neo-fascism,

and the hard-right Northern League.

A significant weakness of the Italian economy is that, while

taxes on labor are too high, those on property are too low. There is no real

estate tax on your main residence, unless it is considered a luxury home. Mr

Draghi’s government moved to adjust the balance by changing the criteria used

in the land registry in a way that would have boosted the revenue from

property. But he ran into determined opposition from the League’s leader,

Matteo Salvini. As a result, the changes will not now come into effect until

2026; and even then, they will not be used to calculate tax liability.

Adapted from an article in The Economist, "The Mario magic"